A shard of deep cobalt, no larger than my thumb, felt impossibly heavy in Grace P.’s gloved hand. The weight wasn’t just glass; it was time, compressed. The light, usually so benevolent through the workshop window overlooking a small, untamed garden, picked out every microscopic flaw, every ingrained layer of time, like accusing fingers. She didn’t flinch. Her gaze, behind spectacles that seemed to magnify not just the glass but its very essence, was that of a surgeon contemplating a living, breathing organ. The leading, oxidized to a dull, almost dead black, needed painstaking removal. This wasn’t about simply replacing a broken piece; it was an act of historical reclamation, a wrestling match with decay that had endured for well over 436 years. This particular window, a majestic depiction of St. Michael slaying a dragon, hailed from a small parish church in Dorset, England, ravaged by a recent storm. The report had listed 66 points of catastrophic failure across the panels, a lamentable tally that belied the monumental task ahead.

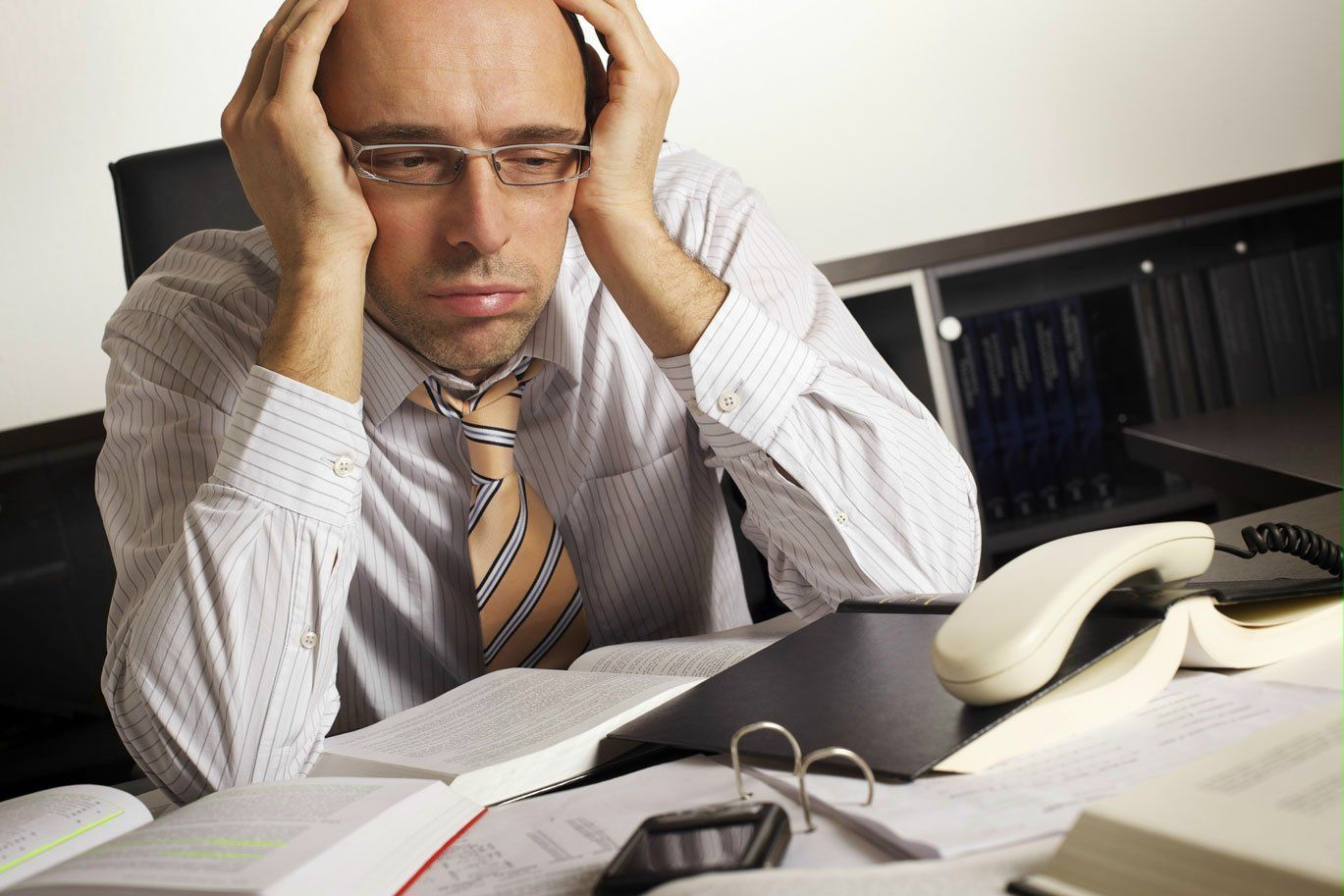

The Bureaucratic Paradox

The frustration wasn’t with the shattered glass itself; that was a tangible, solvable problem. The deeper frustration lay in bureaucratic reports, insurance assessments that reduced centuries of artisanal genius to quantifiable damage metrics. How do you assign a replacement value to light filtered through glass crafted by hands long turned to dust, imbued with the light of countless mornings, the shadows of countless evenings? How do